Is poetry a mirror or a lamp on the world?

If poetry is a mirror on the world, reflecting what is there, then it is surely a funhouse mirror, distorting what is there. Everything is bent, fragmented, stretched, and/or widened. Many free verse poets argued precisely this, that it would be their free verse poetry that would finally provide this mirror on the world, no longer distorted by rhythm and rhyme. The surrealists also made this claim. Who, now, would agree that the surrealists provided any kind of mirror?

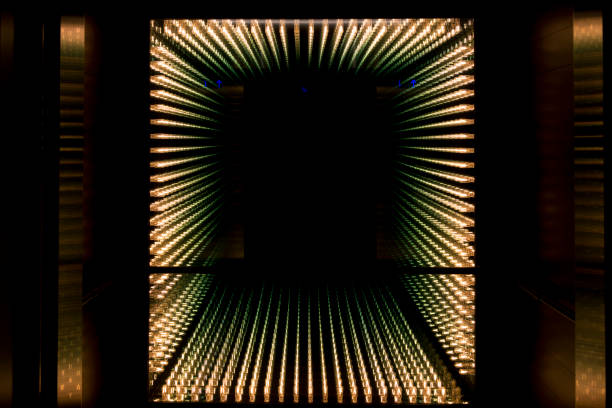

If poetry is a lamp, lighting up the darkness in the world, then it is surely more a moon than a sun. (Ah, but the moon itself is reflective!--a kind of mirror of the sun, imperfect and dimmer.) While the Greeks considered Apollo, the sun god, to be the leader of the Muses, practically every other polytheistic mythological tradition considers the moon goddess to be the source of poetry. Poetry is thus considered to be a product of the moon--a dim light within the darkness, playing with the shadows, perhaps part of the shadows themselves, with the shadows moving, undulating, as the poem's light crosses the darkness, faintly uncovering what lies where people fear to look.

Orpheus descends into the underworld to retrieve his wife from death, but can only return with his poetry. There are many traditions of men descending into the underworld to retrieve something but are only able to return with the gift of poetry.

Plato, in the Allegory of the Cave, instead shows a man ascending out of the cave and into the sun, where he is enlightened. He then returns to the cave to bring the people knowledge of what he saw. He argues that most would reject the philosopher bringing the good news of the sunlight outside the cave. The philosopher thus comes closest to bringing a lamp--but in reality, he's attempting to bring the people to the lamp/sun, which requires persuasion. If you live in dimness and only view shadows, how could you believe in the light?

The poet, on the other hand, can bring the same information to the public without rejection. Why? Because the message is hidden under imagery, metaphor, and sound. The reader is first enchanted by these things, which creates the conditions for acceptance. Of course, this is hardly perfect. There have been plenty of persecuted poets in the world--burned at the stake, in its various metaphorical forms.

Plato wrote in dialogues in an attempt to bring the light of philosophy to the people in poetry. He felt the best poetry was that which was true, and which was trying to get people to see the truth. If this is your goal, remember that you have to do it under a veil.

Too many attempt to make their poetry either a lamp or a mirror. Didactic poetry, ham-handed political poetry--propaganda for a party and an ideology--are almost universally failures. The existence of the brilliant Langston Hughes hardly proves the opposite. Neither you nor I are Langston Hughes. And he had enough sense to write his poems by moonlight.

Having the right understanding of poetry will help you write better poems. For many of you, I am sure that you are already in this kind of lunar headspace and are thus proper lunatics. Some of you are perhaps a little (or a lot) prone to wanting to shine the sun on the world. Alas, such poetry doesn't last, as it mostly annoys readers, preaches to the choir for those who do like it, and really doesn't last. Instead, bring your truths to the world in imagery, metaphor, sound, fable, parables, mythology, and other forms of narrative. Afraid there will be many interpretations of your work? Then write essays. Everyone will bring their own perspectives to your poetry, when it's good, and if you're particularly good (and if you're particularly metamodern), you'll bring multiple perspectives to your reader within your poems themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment