You may be wondering by now why I have primarily been discussing the formal elements of poetry writing. While I have provided some reasoning for my choices--such as the relationship between the brain and rhythm, and the ear and line lengths--there are certainly other considerations when it comes to the practice of any art, including poetry.

The argument that we should write in iambic pentameter, for example, because it's traditional expresses a sort of half-truth. In the same way that drawing and painting using point-perspective has a history--and a recent history, at that--the use of any particular form or structure in the poetry of a given language has a history. In English, iambic pentameter was introduced to English poetry by Chaucer. Old English poems were written primarily in alliterative verse. In each case, the style was developed within a given poetic tradition and came to dominate in typically organic ways, because it was able to communicate something within the language being used.

Many mistakenly believe that because we can typically point to this or that poem as being the first to use a given structure, that means that structure was consciously developed by that person. More typically, the final form is a process of different people trying different things, with one person bringing those various elements together into that final form. While the 13th century Sicilian poet Giacomo di Lentini is the one credited with the invention of the sonnet, its form was an outcome of the poetry composed at the Court of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, including that of di Lentini.

None of this is to take away from di Lentini's accomplishment. The sonnet as a form has since developed a long, strong history, and its form doesn't seem to be exhausted quite yet. Rather, this is to get you to think about how traditions actually emerge. If some single person developed a form or structure, it's easy to dismiss it as arbitrary. If instead it's a consequence of a process, of trial-end-error, and gained stability for good reasons, it's far less easy to dismiss its existence as arbitrary. Something that has evolved and survived is something we ought to take seriously.

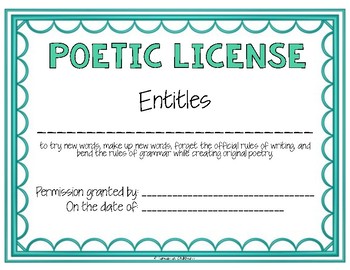

Whenever someone does something weird in a poem--invert syntax, use strange images, violate form, etc.--the common defense is that the poet can, of course, use their poetic license to do what they want. But too often, people use "poetic license" not because they were making purposeful choices, but because they did not know what else to do, and now they need an excuse for what they did.

Did you use an inverted syntax to create a particular effect or, as Milton did, to introduce Latin structures to the English language; or did you do it because you had no idea how to fit what you wanted to say into the form you were trying to use?

Did you use a strange image to challenge readers' conceptual categories and open their thinking to greater complexity; or did you do it because you wanted to be weird for the sake of being weird? (Not that the latter is at all problematic; I'm just asking you to be honest with yourself and others about what you're doing.)

Did you violate form, perhaps even write in free verse, because you had mastered form and are now seeking ways to create meaning through other rules you've created for yourself, creating different kinds of surprises and violations of readers' set patterns; or did you do it because you don't have the slighted idea how to write an iambic pentameter couplet, so are left with writing nothing more than prose with line breaks?

In each of the three examples above, the first scenario was an example of the poet making an artistic choice, of solving an artistic problem. It was made because the poet could in fact make a choice, having the tools available to chose among. In each of the second scenarios, the writer did what they did because they had no other choice, having not mastered the most basic skills of the art of poetry. Are you writing ungrammatical sentences because you have no idea how to write good, grammatically correct sentences? Or are you doing so because you have mastered grammar, and now you want to bend the rules for effect? Only the latter is an artistic choice. The former is merely incompetence.

Thus, the poet must earn his or her poetic license. Master the sonnet, and then show me your free verse. Master grammar, then show me your ungrammatical sentences. Master imagery, then show me your odd images and juxtapositions.

It is precisely because you have to earn your poetic license that this blog focuses on formalism. You cannot deform without knowing what the form is or was supposed to be. More, you need to understand what poetic form and structure do, why poems have across history and across cultures developed similar structures that allow us to universally recognize certain combinations of words as poetry. You are proposing to work within a particular global tradition. That means you have to know and understand what that tradition is. And it means you need to know and understand what poems are and why they have the structures they do. A house has a frame and paint, but that doesn't make it a painting any more than a set of words with line breaks make that set of words a poem.

(It's been said that mediocre artists borrow, but great artists steal. Here is where I stole the above image.)

No comments:

Post a Comment